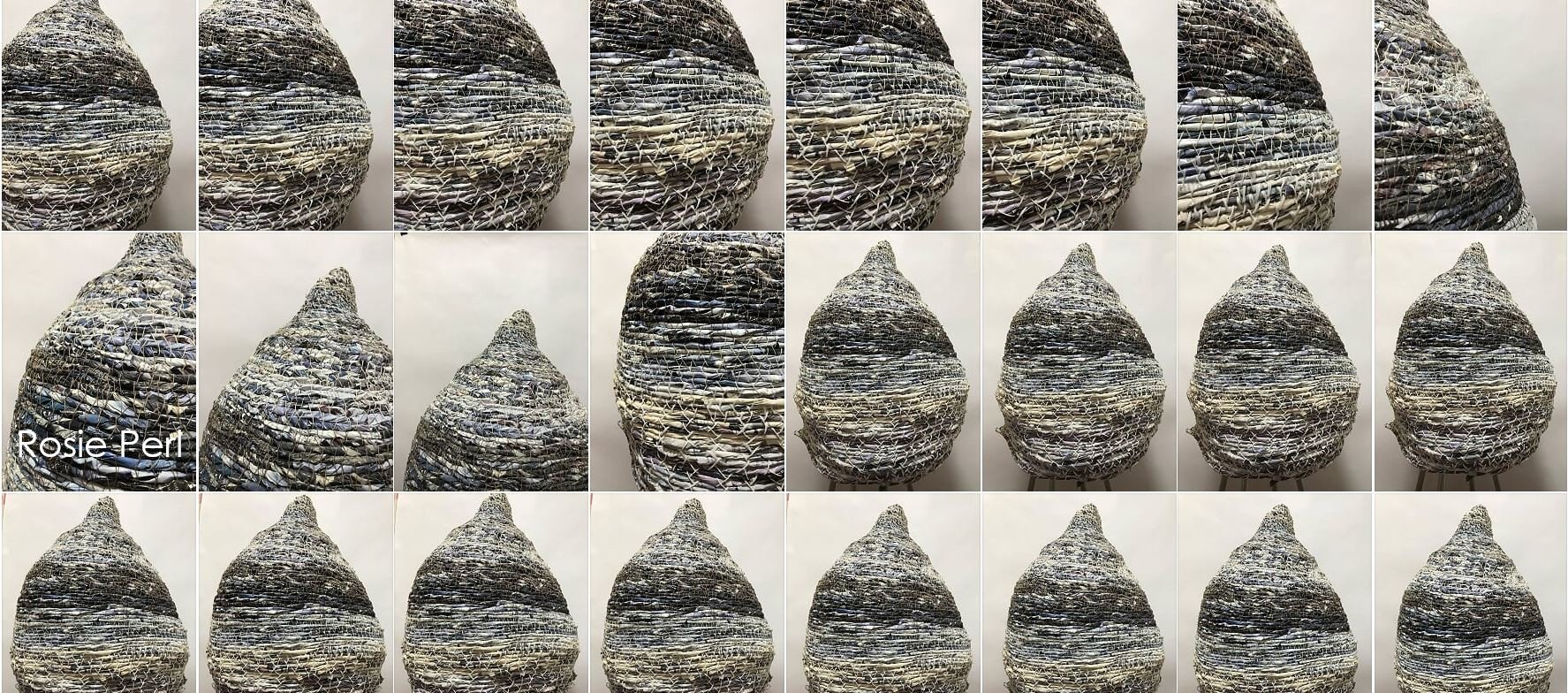

“Venus of Willendorf”, gilded resin, cast from my original sculpture

“There is something so comforting and joyous about prehistoric figurines depicting women, particularly the small, curvy ones, so welcoming in the abundance of their forms, so buttery in their hard, stone body.

Consider the Venus of Willendorf figurine from 30,000 BC, found in Austria in the early 1900s. Unlike most artistic depictions of women, it celebrates the female body without sexualization: Here, this is a woman, it seems to say, she is soft and round, her breasts are large, her hips full, her kneecaps prominent. It’s made of limestone, but you’d be forgiven for feeling you could squeeze it—looking soft and touchable, it seems to defy the physical properties of stone.

The reason why this particular statuette, like the others of similar shape created during the Paleolithic, is known as a Venus, however, runs counter to the above: The name stands for the belief, common at the time of discovery, that this and similar images were goddesses, and that the voluptuous figures were nothing but an eroticized exaggeration of female proportions, an expression of a male, desiring gaze, revered as a divinity of fertility.

Because art was made by men. Wasn’t it?”

Theories abound as to the intention of this astonishment, but it captivated me from the moment I saw it, and it is known and loved across the globe. Its one of those things. To me, it speaks of femaleness with a powerful, objective, yet fondly reflective air, so calm and unwavering in its regard. But when I saw it first, beside the photograph in the book lay the text labelling it as "Venus”, connoting it as something sexy for men to look at and possess. Didn’t seem right. Although its pretty much acknowledged to be misnomer, the whole thing still feels off

I felt that maybe it was about us, women, and how we are, the strength of us, and how all women lay the ground, the experience of being a woman for…other women. In considering this, I quote Annalisa Merelli, in that we might "allow it as the possibility—a glorious one—of a time before history, in between legend and reality, when women loved their bodies with such excitement and passion that they carved them into stone, and made them immortal." I feel at ease with this proposition.

Catherine Hodge McCoid and Leroy D. McDermott posited & published this alternative reading in their academic paper "Toward Decolonizing Gender: Female Vision in the Upper Palaeolithic", which is noted then contradicted by Wikipedia:

“…the figurines may have been created as self-portraits by women. This theory stems from the correlation of the proportions of the statues to how the proportions of women's bodies would seem if they were looking down at themselves, which would have been the only way to view their bodies during this period. They speculate that the complete lack of facial features could be accounted for by the fact that sculptors did not own mirrors. This reasoning has been criticized by Michael S. Bisson, who notes that water pools and puddles would have been readily available natural mirrors for Palaeolithic humans".

I think they missed the point, or covered their ears to the sound of women speaking for themselves, as we take some space to consider that maybe "it placed the artists in a society that depicted and celebrated the female body not for erotic, male pleasure, but as something with its own intrinsic value and power".

Good shiny.

People have always worn jewellery, its across every culture & belief system and its something we all need, for whatever reason that makes sense at the time of it’s acquisition. This sculpture is something I feel close to; I can certainly identify with it’s shape (totally familiar with pregnancy) & I feel connected to it in a way I cant articulate. When I cant articulate in words, I endeavour to in imagery, so in using this piece in jewellery, which is intrinsically valuable & very personal, it feels like I’m honouring its emotional value

In my art practice, there are images which have reoccurred throughout that symbolise ideas, emotions, sensations & comprise my visual vocabulary. I’m always working towards some mythical higher ground, proposing connections and finding new problems in an internal debate where I cant express the terms of the mission in any other way than by my practice itself. This current work is the next roll-over. Working the materials and evolving the processes is where I find myself

The Venus and the Mona Lisa, so inscrutable.

And some wholesale copy via Artsy:

“Carved in an era before written language, there is no clear proof about what these figurines represent. The most accurate clues scholars have about what the statuettes portrayed and why lie in the formal qualities of the figures themselves. Nearly all of them are petite—several inches long and diminutive enough to hold in a hand or string onto a cord (some even contain carved loops, seemingly for this purpose). The people who forged them led a nomadic life and some scholars conjecture that they intentionally made the figures small and light for easy transport. This hypothesis points to the personal value of the figurines and their possible devotional use. In this reading, the statuettes weren’t objects to be discarded, but ferried with their makers—held or strung close to bodies as they roamed from place to place.”

Some “may be convinced that the statuettes represent fertility, but other scholars have made convincing arguments for their function as goddess figures, religious or shamanistic objects, or symbols of a matriarchal social organization.

The possibilities for interpretation seem endless, but as the archaeologist Olga Soffer has suggested, there should be limitations. Soffer warned against analysing the figurines in terms of “18th-century Western European art.” While the misleading moniker “Venus” seems to have stuck, legions of archaeologists and historians continue to reinterpret the cache of these statuettes, pushing them beyond narrow labels.”

Something to think about